FOSTERING A VIBRANT RENEWAL OF JUDAISM IN POLAND

Rokhl Auerbach, the Yiddish Shmoozers, and Jewish Cultural Resistance to Regime Change in America

Gelya Frank[1]

Yiddish Shmoozers (in Translation)

For submission to: In Geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies

In 2003, an American president used the military term ‘shock and awe’ to describe the American-led invasion of Iraq, which began with a blistering air attack on Baghdad.

Shock and awe refers to the strategy of ‘rapid dominance’ over an enemy through overwhelming power and force.[2] Its goal in Iraq was regime change.

Unbelievably, a president-elect of the United States who had promised the country ‘shock and awe’ took office on January 20, 2025.[3] His Day One barrage of Executive Orders, some clearly unconstitutional, calls to mind the War in Iraq. The goal then was regime change, and it seems that way now.

Are we witnessing an authoritarian takeover in real time? How is it that political opponents of the ruling party in a democracy are being treated as enemy combatants? If this is war, then let’s prepare ourselves. To the barricades! Yidn, lomir leynen! Come on, Jews, let’s read!!

Even more radically, take our community’s tear-stained copy of The Diary of Anne Frank from the hands of our children. Let them read selections from Warsaw Testament. Talk with them about self-help, community organizing, solidarity, and survival.

Freighted Legacies Webinar

Dr. Samuel Kassow’s Translation and Framing of Rokhl Auerbach’s Warsaw Testament

April 27, 2025 / 10AM Los Angeles / 12N Chicago / 1PM New York / 6PM London / 7PM Warsaw / 8PM Jerusalem

*CLICK HERE* TO REGISTER FOR THIS WEBINAR

The Freighted Legacies webinars welcome Dr. Samuel Kassow’s discussion of his translation of Rokhl Auerbach’s Warsaw Testament. We are looking forward to a great presentation of this moving historical document.

As a special feature, we would like to invite you to read about a conversation (shmooze) in early January 2025, by Yiddish Shmoozers in Translation, reflecting on the contemporary significance of Rokhl Auerbach’s Warsaw Testament.

In the following video Rabbi Beliak shares supporting content regarding the April 27, 2025 webinar.

Watch this video to learn more.

Rokhl Auerbach: Writer, Aid Worker, Moral Witness

Rokhl Auerbach: Writer, Aid Worker, Moral Witness

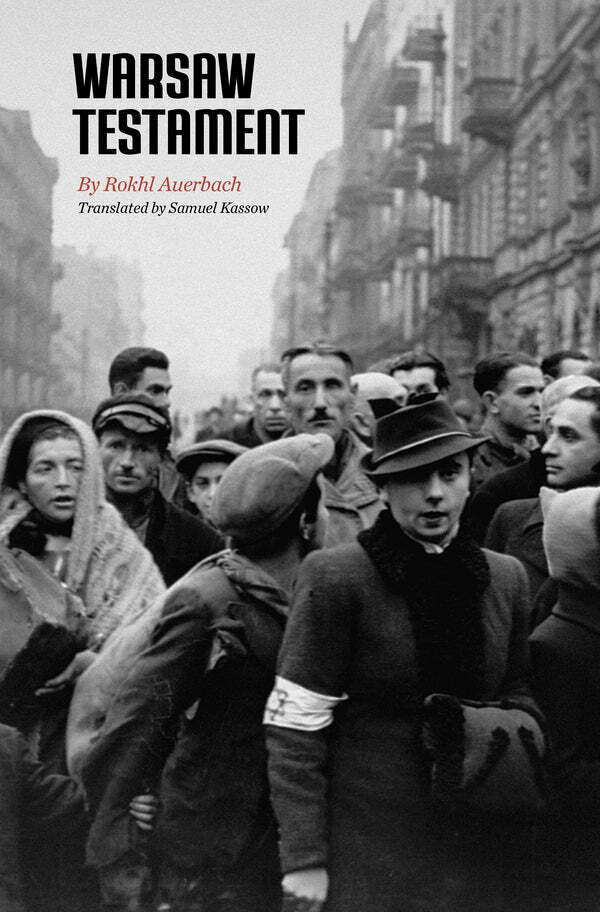

Among a welcome cascade of Yiddish books newly translated into English, Warsaw Testament calls out to be read now.[4] Writer Rokhl Auerbach compiled and structured the bulk of the book’s narrative in Tel Aviv in 1973, drawing on her earlier eyewitness notes on Jewish suffering and resistance under Nazi occupation two decades earlier. In Tel Aviv, she wrote:

Driven by an uncontrollable impulse, I wrote in secrecy and solitude. . . . In the autumn of 1943 and during the winter of 1943-44, working between midnight and 5 a.m., I wrote two works: They Called it Resettlement, on the Great Deportation of 1942, and what became, as I kept adding more material, an early draft of this book. In the daytime I would hide my notebooks at the bottom of a drawer and cover them with the apples, pears, dark flour, and barley cereal bought with the ration cards. (p. xlii).

In Warsaw Testament, historian Samuel Kassow translates Rokhl Auerbach’s 1973 text, adding an Introduction, endnotes, and biographical sketches of individuals that the writer mentioned. Kassow emphasizes how rare and valuable Auerbach’s work should be viewed as a primary document of the Warsaw Ghetto written in real time.

Warsaw Testament is an exceptional eyewitness report of life in the Warsaw Ghetto, but also more than a resource for data extraction. Because of its coherence and depth, the book is less like a journalist’s account and more like an ethnography written by a trained participant observer immersed in this most challenging field site every day for more than five years.

Like novelist Chava Rosenfarb, who wrote the magisterial Tree of Life trilogy about life in the Lodz Ghetto, Auerbach tells moral stories. She reports on everyday situations, personalities, perspectives, and acts with both passion and scrupulous objectivity. Her rigor as a reporter extends to descriptions revealing who she was, what she did, her outlook, her choices.[5]

Rokhl Auerbach was born in 1899 in Galicia, now Ukraine, and spent her young adult years in Lemberg/Lvov/Lviv. The online Jewish Women’s Archive biographical entry about Auerbach suggests viewing her life in three phases.[6] In the first phase, Auerbach studied in Polish at the Adam Mickewicz Gymnasium in Lemberg and at the Jan Kazimierz University of Lemberg where she completed graduate work in psychology, philosophy, and general history.

She began writing for the Polish and Yiddish press in Lemberg in 1926. In this same period, Auerbach cofounded the experimental and regrettably short-lived Yiddish literary journal Tsushtayer with philosopher and poet Debora Vogel. She also co-edited and published work in Yidish, another journal of the modernist Yiddish cultural movement in Galicia.[7]

The next phase began in 1932 with Auerbach’s move Warsaw to continue her writing career in Poland’s vibrant capital. Right after the Nazi invasion of Poland, Auerbach was recruited by historian Emanuel Ringelblum October 1939 to work for the Oyneg Shabes, a secret organization that Ringelblum organized with funds from the American Joint Distribution Committee (JDC).

The Oyneg Shabes existed for one purpose, to compile a comprehensive archive documenting the Warsaw Jewish community’s lives under Nazi occupation.[8] Ringelblum held meetings with the group’s members on Friday nights and Saturdays, hence the name Oyneg Shabes, which means ‘Joy of the Sabbath’ in Hebrew, with Polish Yiddish pronunciation.

The 60 members of the Oyneg Shabes, including Rokhl Auerbach, assembled an enormous archive of some 6,000 documents or 30,000 pages. It included Nazi orders, posters and handbills, Jewish interviews and testimonies, photographs, paintings and drawings, manuscripts and musical compositions, as well as reports that Emanuel Ringelblum commissioned from writers like Auerbach.

Samuel Kassow’s earlier book Who Will Write Our History? is the story of Emanuel Ringelblum’s work with the Oyneg Shabes, including Ringelblum’s abrupt decision in 1943, during the deportation of Jews to the concentration camps, to bury the archive. [9] The trove was stored in metal boxes and milk cans and buried underground in three caches.

After the war, in 1946, Rokhl Auerbach and Hersh Wasser, two of only three surviving members of the Oyneg Shabes, led the Jewish Historical Commission of Poland to the first burial site, where ten metal boxes were recovered. The second cache was uncovered in late 1950, but the third and final cache was never found.[10]

Rokhl Auerbach never stopped her public insistence on the moral necessity to recover the archive’s missing cache. Her role is highlighted in the documentary film, Who Will Write Our History, directed by Roberta Grossman and co-written with Kassow, based on his book.[11]

Events in Warsaw Testament begin with the night of August 31-September 1, 1939, as Nazi Germany invaded Poland with an aerial bombardment. Auerbach closely describes the reactions among her acquaintances among in Warsaw’s writers and artists. It was a moment of enormous fear and uncertainty in which quick decisions led to fateful consequences.

Auerbach’s unblinking, deeply felt reporting in Warsaw Testament continued throughout the establishment and destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto (1940). She describes the deportations to Treblinka and other death camps (starting in 1942), the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (1943), and the liberation of Poland by Soviet-Allied forces (1945).

Ringelblum recruited Auerbach to be the director and manager of a soup kitchen organized by the Jewish mutual aid organization Aleynhilf (Yid., self-help). She directed the staff that cooked and served meals using industrial-size cauldrons. She also oversaw regularly-occurring cultural events at the kitchen that brought together various groups within the community. Ersatz coffee and ersatz cake were served.

Any writing Auerbach did occurred at night, after working at the soup kitchen. This remained her job up until the deportations of 1943, when Ringelblum decided to bury the archive. He also ordered her to leave the ghetto and live in arrangements he found for her on the Aryan side. Auerbach’s second tranche of writing, including the manuscript of the book eventually translated by Kassow and titled Warsaw Testament, was done on the Aryan side, alone and at night, to evade discovery.

Auerbach’s duties for the Aleynhilf gave her a unique vantage on a wide swath of the community. They also demanded an almost unimaginable degree of self-discipline and courage. Every kind of person crossed the kitchen’s threshold and all were desperately hungry. It was Auerbach’s responsibility to obtain provisions and supervise recipes, while food supplies dwindled, especially food with nutritional value.

As an administrator and worker, Auerbach had a wide range of face-to-face relationships and knowledge of people’s unique hardships on a daily basis. It is not surprising to me that after the war she is said to have argued tirelessly on behalf of recording and listening to survivors.

Yet Auerbach describes how she had to turn down requests for extra rations. She watched her customers slowly starve because there simply was not enough food to keep everyone alive. And she struggled internally because of orders from Ringelblum to provide extra food for a few select individuals whose persons or testimonies he considered essential to preserve.

Auerbach states in Warsaw Testament that when she started the kitchen job, she resolved to be absolutely fair and impartial in doling out rations. One of the most touching parts of the book is her admission that it was not humanly possible for her to always enforce that rule on herself. Her reasoning and dealings with known workers’ theft of food and known customers’ finagling of extra rations are important to read.

The third period in Auerbach’s life concerns her post-war life in Israel, where she worked for the Yad Vashem museum, vigorously advocating for the collection of survivors testimonies and their incorporation as legal testimony during the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961. But that part of her story takes us beyond our focus here on reading under regime change.

An Experiment in Double-Consciousness Reading

The buzz in the Jewish community about Warsaw Testament and news of upcoming online lectures by Samuel Kassow reached the Yiddish Shmoozers (In Translation) in late 2024, in time to schedule an event to kick off our 2025 programming. The Yiddish Shmoozers is an online English-language group of which I am an organizer, blogger, and discussion facilitator.[12]

We received permission from the Yiddish Book Center to advertise its January 23, 2025 talk by Kassow as a warmup for our discussion of Warsaw Testament on January 26. As these dates approached, mindful of the Yiddish Shmoozers commitment to Yiddish culture as a resource for our time, I emailed members with a proposed experiment in ‘double consciousness reading.’

The experiment acknowledged my own and others’ growing fear and uncertainty as the Inauguration Day approached. The incoming president’s outspoken promise to be a dictator “only on Day 1” (one day too many) was awaited warily, with trepidation, along with his threats to stun the country with ‘shock and awe’ tactics from the Oval Office.

The concept of ‘double consciousness’ was introduced by America’s great sociologist of race, W. E. B. DuBois, in The Souls of Black Folk in 1903. DuBois talked about his sense of ‘twoness’ as a black man who must necessarily always be aware in his everyday life of how he is seen from society’s dominant white perspective.

The Yiddish Shmoozers reading experiment takes for granted Jewish familiarity with that sort of ethno-racial ‘twoness’ and proposed something a little bit different. The Yiddish Shmoozers were asked to work simultaneously with the historical experiences described by Rokhl Auerbach and their own immediate experiences of this country’s political upheaval.

Of course, ‘good readers’ will always reflect on the meaning of a text, both the author’s meaning and the meaning to them. But the Shmoozers January 26 experiment asked for a highly specific, disciplined application. The task:

Let us bring a ‘double-consciousness reading’ to Rokhl Auerbach’s Warsaw Testament. Let’s read for what happened then. And what’s happening now.

Please be so good as to sharpen your pencils and note:

1. How did the diverse Jewish individuals mentioned by Auerbach imagine, perceive, and understand the situation?

2. What groups and resources were available to them as they decided what to do?

3. Let us reflect on and discuss our own reactions to and observations of the changes unfolding around us.

The fear? The uncertainty?

Warsaw Testament’s strength is in reporting what people felt, thought, and did–step-by-step, in real time. Join us in reading Warsaw Testament as a resource for thinking about America’s situation and ourselves in real time.

Sixteen individuals from around the country, ages 46 and up, Zoomed in for the scheduled two-hour conversation on January 26. About an hour of highly focused conversation was recorded, with the remaining time taken up by back-and-forth chatter and technical delays.[13]

As an anthropologist trained to use and teach qualitative methods for social science research, I worked with the Zoom transcript in order to listen again, more closely, to how the Yiddish Shmoozers approached the reading experiment overall.

The expectation that the Shmoozers might be experiencing fear and uncertainty a week after the Inauguration was prescient. The conversation oscillated between two poles. The role of the facilitator was to continually remind participants to bring themselves back to task—that is, to interrelate the two sides of their conscious inquiry.

On one hand, the Shmoozers avidly discussed Rokhl Auerbach as a heroic figure. They were affected by her writing about people and events in the Warsaw Ghetto and by what she was able and unable to do as director of an Aleynhilf soup kitchen.

On the other hand, the Shmoozers tended to veer into fearful characterizations and speculations about the country and its politics. Speakers expressed uncertainty, anxiety, and dread about how they might take effective action.

Timothy Snyder, a leading historian of Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism in Eastern Europe, wrote this warning in his 2017 book On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century:

The Founding Fathers tried to protect us from the threat they knew, the tyranny that overcame ancient democracy. Today, our political order faces new threats, not unlike the totalitarianism of the twentieth century. We are no wiser than the Europeans who saw democracy yield to fascism, Nazism, or communism. Our one advantage is that we might learn from their experience.[14]

The Shmoozers were asked to reflect on their experience of the incoming administration’s ‘shock and awe’ tactics and on how Auerbach’s experience could help us think and act. What follows are excerpts from the Zoom transcript, follow-up emails, and texts, organized topically as they emerged on and after the January 26 conversation.

The Conversation on January 26

My report of the conversation uses Timothy Snyder’s pedagogic strategy in On Tyranny. The topics and themes from the Shmoozers experiment in ‘double-consciousness reading’ are presented aphoristically as seven practical lessons.

- Commit to building new relationships of solidarity

Caroline, a professor of philosophy, kicked off the conversation with “one thing that kept jumping out to her” in Rokhl Auerbach’s descriptions, the need to work with potential allies despite past conflicts. She said she was inspired by Auerbach’s varied relationships with workers and customers at the soup kitchen that cut across the lines of national/ethnic identities, political affiliation, class and status, age, education.

Again and again, in the book, people who in the years before the war had big differences politically, religiously, and ideologically found themselves in community under the Nazi occupation. They found themselves thrown together in the soup kitchen, for example. So I feel that now my antenna need to be out for how we can work together –and even if we can work together—in my faculty union, for example.

She continued:

Over the years, it’s been difficult to build the links from our campus chapter of the union and the local blue-collar unions. Even though, in principle, we belong on the Central Labor Council. I guess this is something that I personally, I’m going to try to do. To be somebody who shows up from academia at the Central Labor Council meetings. And this is inspired, in part by reading Auerbach. I’m thinking, okay, I’ll do this.

Mindy, a scholar of English literature, brought up Auerbach’s description of the soup kitchen she managed at Leszno 40:

Whenever she can, Auerbach shows partnerships between Poles and Jews. As in the soup kitchen, they work together in smuggling food from the Aryan side into the Ghetto.

Caroline later identified a paragraph in Warsaw Testament about forging working alliances among previously disparate groups. It occurs at the beginning of Auerbach’s story about the soup kitchen.

The Aleynhilf took over all kinds of Jewish institutions, including party headquarters, offices, welfare organizations, schools, and unions, and it brought together and employed large numbers of communal activists along with the Jewish white-collar intelligentsia. All other forms of public, political, and cultural life were forbidden. But in time Jews resumed these activities under the protective cover of the one type of organization that was allowed (p. 38).

Reading this paragraph had inspired Caroline’s opening comment about stretching past her comfort zone in order to ally with blue-collar union members as a representative of her faculty union, although the groups did not share identical concerns and had even been in conflict, within their local umbrella labor organization.

Lydia, a multi-media artist, recalled Rodger Kaminetz’s book, The Jew and the Lotus, where the Dalai Lama asked a delegation of Jews to advise the Tibetan Buddhists on how to avoid a cultural genocide. Kaminetz responded by describing the Passover seder as a ritual of presence-in-remembrance. Actually, a kind of double-consciousness reading!

If there is a group of Shmoozers would like to dedicate themselves to this kind of discussion, I would like to see us interface with Latino, trans, and other groups currently under threat.

Mindy reminded the group that once the deportations of Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto had started, Ringelblum had Auerbach move to the Aryan side of the city. Mindy asked the group how she was about to move back and forth without being apprehended. Rosalie, a cultural anthropologist, reminded the group that Auerbach was able was able to speak Polish fluently, like a native, having been raised as a young person in an atypical village environment. Consequently she could relate and blend into the Aryan population:

She spoke the language very well. She had tremendous familiarity with the way people, common everyday people spoke. And so she didn’t call attention to herself.

Lena commented:

It was for some people relatively easy to go in and out of the ghetto. There were a lot of Jews who spoke perfect Polish, assimilated Jews who didn’t speak with an accent or didn’t even know Yiddish.

Shayna noted:

Apparently she also had help on the Aryan side. Ringelblum was in contact with people on the Aryan side who helped.

2. Watch how people get and use information. Work on counternarratives.

Rochelle, the facilitator, had blogged with the group about Auerbach’s description of the first moments of the Nazi air bombardment of Warsaw. Some people fled. Others made decisions to stay. Information was lacking. Confusion was rampant.

Nancy, a psychologist, brought up the topic of how people experiencing fear and uncertainty construe information and act on it.

One of the very striking things in Warsaw Testament is how people seek information and are frequently interpreting what they receive as information incorrectly. And building fantasies or narratives of hope or despair, which may or may not, at a given moment, be warranted. . . . So I think that we’re immediately drawn to compare them with social media in our own time. Those who oppose regime change need to find effective ways to communicate effective counternarratives.

Lydia picked up this thread about the need to offer counternarratives and the difficult of doing so in the current media environment.

When it comes to Facebook, it’s effective to have our bubble or companionship and to strengthen each other’s discourse. But, at the same time, we know that Facebook is a platform that circulates so many lies. . . . I was struck by the last paragraph on p. 107 about the SS man who was confounded by the Jews’ efforts to survive. “Why haven’t the Jews gone mad!?” he shouted. The answer, Auerbach explains, is that there was a statistical study in the first year of the war showing the suicide rate among Jews had fallen markedly compared to the pre-war period. Auerbach writes that this happened because in an extraordinary time the Jews mobilized inner reserves of strength and psychological resistance that in normal periods remains repressed. I find that really interesting. I wish somebody would take that sentence and run with it.

If counternarratives are stories based in fact that disrupt stereotypes and lies, then it is also important, Rochelle suggested, to question one’s own certainties and entertain self-doubt. She cited from Auerbach’s description of her writer friends’ reactions to the invasion:

That same night certain colleagues burned books and journals containing anti-Nazi material. Despite the tragic situation, the poet Reyzl Zychlinski could not suppress a laugh when she told me about a certain young poet who, on the night of September 5-6, ripped out each page of his first published book of poems and tossed them one by one into the oven. He thought that as soon as the Germans took the city their first priority would be to barge into his rented room and grab the little book with his anti-Nazi poems (p.13).

Lydia demurred in a subsequent email exchange with Rochelle.

The tragicomic anecdote that Reyzl Zychlinski shares about a young poet tearing up his book of anti-Nazi poems would be less amusing today. Today, February 7, I saw an article in The Washington Post about digital surveillance that says that the government in the United Kingdom ordered Apple to provide it with access to every single encrypted thing that’s on iCloud. Is it only a matter of time before that becomes true of the current administration here?

Joanie, a former lawyer and stockbroker, sent an email commenting on this topic.

I’d like to suggest that for myself, I need to learn a lot about AI (Artificial Intelligence). And how to wheedle myself into conversations with people that I would never otherwise have a conversation with, to bite my tongue and at the same time try to help sculpt counternarratives about what’s true and not true. Sculpting messages that somehow get through the filters and present a different reality.

3. Be realistic about the media environment but don’t allow it to overwhelm you

Shayna, an independent learning designer with an academic background in history, pointed to social media’s dependence on MAGA oligarchs and the growing challenge to effectively circulating counternarratives.

I think is one of the ways in which our current situation is different than Nazism and Mussolini’s fascism has to do with social media, as Lydia mentioned. We are in the era of the internet and social media is pretty much in the hands now of the MAGA group. It’s something the world has never experienced before and poses a unique challenge. We can’t really look in the past for solutions because they didn’t have this problem. But we have to find ways to counteract this mass of lies that is broadcast in seconds, in minutes, all over this country, all over the world. Anyway, I think that this is one of the ways in which we need to look forward and look to our creativity, since we just cannot find the answers in the past.

Lydia responded:

Well, creativity. But also how do we fight the algorithms?

Shayna replied:

We have to do both: Resist and find new ways at the same time. The challenge is massive. It’s controlling the levers of information worldwide and 90% of that massive thing is lies and disinformation…. How do we alter the communication paths? It’s huge and it’s overwhelming and it’s depressing, but I see it as a challenge. And I also feel that we can’t stick our heads in the group but try to find ways to meet it.

Mindy mirrored Shayna’s anxiety about how to effectively reach the public with counter-messages:

The places where most of us get news we think is reliable —like podcasts we believe in or believe in for the most part and print journalism like The Atlantic—they aren’t snappy, they’re not sexy. The messages don’t travel quickly. Can we deliver? To thousands and millions of people in a reliable way, without minimizing, simplifying, and obscuring the truth.

Rochelle, the facilitator, noted that demoralization about social media might be distracting the Shmoozers’ conversation from the ‘double-consciousness’ task of reading Rokhl Auerbach.

Maybe that’s escaping a bit from the task, situation, and feelings right in front of us. What are we thinking and feeling? And, today, what can we do? I’m just wondering whether dwelling so much right now on the massiveness of the problem is also a problem.

Shayna responded:

It’s demoralizing to really change the dynamic. It’s awesome in the worst way of awesome, what people believe all over this country. But I think we need to think about it a lot and creatively to see if there’s any more immediate way that we can incorporate something into our lives and the lives of people we know. I have friends who just don’t want to watch the news.

Rochelle commented on one way she has begun doing something by connecting with organized electoral political action:

I went to an in-person meeting last weekend of the group www.indivisible.org. Over 100 people showed up at a church social hall to talk about democratic strategy going forward. The strategy is to regain Democratic Party seats and votes in Congress and in other critical elections around the country. They polled the group on how people are coping. Most people responded that they had stopped watching the news on television although otherwise continuing to follow what was being reported.

Lena also brought the conversation back how she is feeling and what she can do now.

I’m pretty terrified myself. And it’s one of the reasons I don’t really like to watch the news, because sometimes my stomach just cramps physically when I hear it.

Victor, an engineer, discussed making choices to filter out the noise on social media:

We always have a choice not to follow the social media. I don’t have Facebook and so forth. I don’t really need to go and argue this online.

Shayna reiterated her need to focus on something she could actually do.

I don’t find the feeling of not being able to do anything very comfortable in times like this when there’s social upheaval. Chicago just got hit with ICE (U. S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) raids tonight. I saw it on the news before I got on here. It’s a very personal question. I’m not 23 years old and I don’t have the energy that I did then. And yet I can’t do nothing.

Joanie commented:

I think there’s nothing wrong about asking the question, When is it time to take more drastic action? Brave individuals in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising put aside their normative behavior to counter the unfettered, lawless actions of the oppressors.

4. Observe and listen with compassion, be a helper, and help the helpers

Rochelle brought the group back to task.

What would Rokhl Auerbach say? What could we use from our reading of Warsaw Testament to get through this?

Shayna answered:

In her writing, Auerbach has such compassion and empathy for every different person, whether the people are disengaged or whether they are super-attentive to what’s going on. I mean, she has amazing human compassion. In situations where I feel that people are speaking or acting irrationally, without knowledge of the facts, and in my opinion immorally, I tend not to have so much human compassion, so I know where I need to work. But that’s not a way to solve the problem, either.

Suzanne, a psychoanalyst, picked up the theme of compassion:

Don’t we have an obligation . . . I have to believe, and this may be naïve on my part, that there are going to be consequences that ordinary people will experience because of the MAGA policies. Things actually done that will be deleterious to the lives of ordinary people and that they will observe this. I think that something to do that must be done is to point out the awful consequences of such things. I had an experience which I didn’t know how to process during the presidential campaign, when I was so much believing in Kamala Harris and her ultimate triumph. I was at the supermarket and woman my age was standing kind of transfixed. I thought she didn’t know her way around the market, so I asked if I could help her find something. And she said, “No, no, no. It’s the prices.” It gave me just this moment of doubt, which unfortunately was borne out. I think we have to notice what’s actually happening to people. People really need just to notice and observe. And testify to what they are, in fact, observing and experiencing.

Denise, a retiree and self-described perpetual student, picked up the theme of compassion, drawing on her engagement with Buddhism and teachings about the importance of helpers.

This isn’t from Rachel Auerbach, but I get an email from time to time from the Buddhist meditation teacher Jack Kornfeld. He wrote about Mr. Rogers being a bodhisattva, especially to children. Mr. Rogers’ mother used to tell him in times of trouble, look for the helpers. You could see it recently in the Los Angeles fires. I mean, the political situation is a different kind of fire, people can become helpers in terms of the metaphoric fire that we’re experiencing in the country. I’m thinking about focusing on people of goodwill who are going into bad and difficult situations to help where they can. And that being on this screen are many people who are willing and capable of being helpers.

Caroline’s next comment integrated the concept of ‘being a helper’ with Auerbach’s descriptions of collective ‘self-help.’

It shouldn’t be lost on us that the organization that Auerbach worked for was the Aleynhilf. Self-help. It was self-help in that because the Aleynhilf pushed back against and resisted the co-opted Jewish council, the judenrat, that the Nazis set up. Self-help means the independence to organize to meet the needs that are on the ground now as best we can. That includes the need to help those who are helping, like the people trying to provide legal help to those threatened with deportation.

She harkened back to the McCarthy period of Senate hearings, purges and blacklisting of liberals, homosexuals, Communists, and others. People were targeted for investigation, fired from government positions, and banned from jobs, including in the military. This was experienced by parents of those Shmoozers born or raised in the United States and they left a legacy of survival, although lives were disrupted and people suffered.

The lessons that go from generation to generation include those lessons of doing what we can. And one more thing: It’s true that we are swimming in these enormous baths of falsehood and propaganda but it’s also true that half of our fellow countrypeople are on the side of democracy and not fascism.

5. Start thinking about where you can have the most effect

The impulse to do something, and the decision about what to do, and when, were discussed by Carmela, a retired Reform congregation rabbi, and Victor. Carmela came to the discussion as a guest and “was just going to be quiet and audit,” but spoke up about her fears and the risks of resistance.

What am I going to do when they arrest Bishop Marianne Budde? Or Rachel Maddow? I am really terrified.…When the Muslim ban happened in the opening days of the first MAGA administration and people swarmed the airports, I didn’t go. But if it happens again, this time, I will.

In a later email, Victor discussed the most meaningful distinction to him between Rokhl Auerbach’s situation and our own. This is the fact that fascism is now an internal threat from within the American system rather than externally imposed. While he protested the Muslim ban in the first MAGA administration, he reflected that is unlikely to do the same after October 7.

In the Warsaw Ghetto, the Jews were united under the external threat of Nazism. The Jews in the United States in 2025 are not united in agreeing that what we are facing is fascism. On Inauguration Day, most of the Jews that I know were “happy” with the changes that are happening in this country because it serves their beliefs. Although I don’t agree with them, I understand them. In 2017, when the was issued against ban against immigrants from Muslim countries, I went out, actively protested, and even spoke at one gathering. If it happens again, I’m not doing it, this time.

When Rochelle asked him why, Victor responded :

Well, to be honest, my views were affected by the response to October 7th. There are definitely defining moments when an event happens that flips the course of history upside down: 9/11, the U.S. invading Iraq on 3/20/03, Russia’s war on Ukraine on 2/24/22, and now 10/7/23. The reaction of many groups to Jewish global pain on that day angers me to lend my voice. Jews stood by most minority groups since the Civil Right Movement. The fact that no one came to our side but instead perpetuated antisemitism after 10/7 prevents me from continuing my efforts, at least for the time being, I am waiting to see all the hostages that are alive and those that are (unfortunately) dead to be returned first. It is now three weeks after the Inauguration, and I am watching how our government is being dismembered. This does make me want to get back involved, because at the end, losing democracy is too much of a price for me. However I am not sure how to do this. Saving democratic institutions such as the National Parks, Department of Education, and USAID are on top of my list.

Lena, a poet, led the conversation into the hard choices that Auerbach faced and the external constraints on her ability to act.

What I want to say takes off a bit from what Caroline said earlier. I thought one of the interesting things about Auerbach was her frustration and realization and acceptance of the fact that she couldn’t save everyone. That she really had to make hard choices. And that she wasn’t going to defeat the Third Reich by herself. That she could only do what was in front of her, at that moment.

It reminds me and echoes what a friend said about the point at which you really have to start thinking locally. You have to start thinking where you have the most effect. And you have the most effect locally with local governments, state government, city governments. There’s a lot of resistance already there historically to some of the major issues now emerging.

So I think that makes it less overwhelming, if you have a perspective and can actually do something physically . . . go to the capital, talk to a congressperson . . . .The idea is we can be more effective when not thinking about how overwhelming it all is.

Nancy sent an email later to add three points that concerning effective action:

My first point has to do with my pessimism in reaching people who do not share our views, given that people are generally unreceptive to viewpoints other than their own and do not seek them out. My second point has to do with the multi-pronged attack on our values making it difficult to identify or focus on the most critical among them and temporarily having to forego pushing for some important changes (I don’t know how we’d begin to make these decisions). My third and last point concerns someone’s comment that individual action might not be too successful in accomplishing our goals, other than at a very personal level, and that reliance on a well-organized legal pushback could be critical.

6. Recognize cultural work as a form of resistance

Lena made this final point summarizing a main thread in Rokhl Auerbach’s book, in which she intentionally focused on writers and artists:

The thing that I thought was so incredible about Auerbach was her description of how valuable cultural work was for people and how they needed it, sort of, to survive. The plays, the theatre, the music. I thought that was really powerful. I don’t know how many people have read The Book Smugglers.[15] It’s about people in the Vilna Ghetto who defied the Nazi seizure of the great collections of Jewish books by taking books one by one on their bodies and hiding them in bunkers or smuggling them across borders. There was a lot of tension at the time because they were trying to save our cultural articles. People said, ‘Why aren’t you trying to bring us food instead?’ That tension between the material and the spiritual that Auerbach talks about is very, very intriguing to me. And maybe that’s also got to be part of the struggle, to try to maintain that and not give up on it. To maintain some space where we can actually breathe easily. And appreciate whatever it is that we like in our lives.

A written reflection by Julie, a graphic artist who was quiet during the Zoom call, spoke to this point:

I was glad I joined the group for the discussion. I know a little about Rokhl Auerbach from taking Sam Kassow’s seminar but have not read her work directly. I cannot comment on how her writing was layered onto current events, but it seemed others were making sensitive parallels. Even yesterday’s news of the “pause” on spending for health and education and beyond. . . . I was moved by the discussion, with so many intelligent people on one Zoom expressing their heavy concerns about the state of affairs. Each day brings another shock. As an aside, I’m not sure where I would leave/run to–seems like there are issues everywhere on the planet and civility is out the window. Mostly, I hole up in my studio working and try to stay as positive as I can.

7. Stand in the lineage of Yiddish responders

Gabriel, an activist Reform rabbi, closed the conversation with a reminder that Ringelblum, Auerbach, and many members of the Oyneg Shabes drew directly on their own and their predecessors’ experience of assistance to Jews under duress. He cited the sudden deportation of about 16,000 Polish Jews living in Germany, most to the Polish town of Zbąszyń (Ger., Bentschen) the night of October 27-28, 1938. Although, at first, some were able to rejoin relatives inside Poland, others were blocked by a Polish government order, creating a crisis situation.

I repeat that Ringelblum and many of his associates were not newbies in responding the unprecedented assaults. They had been focusing on these skills. Rokhl Auerbach had experts to inform the staff that she built to feed the community, drawing on Aleynhilf ‘s experience and growing fund of knowledge born out of necessity. As a journalist who kept abreast of events on the Jewish street, Rokhl herself had been following the events and organization by Polish Jewish groups, as had Ringelblum when Jews were dumped over the border in the town of Zbąszyń.

Nukhem, an historian, decided not to come to the January 26 meeting despite his interest and his years doing human rights work in the challenging area of immigration. In an email he mentioned, however, another recent eyewitness account translated from Yiddish to English, A Ukrainian Chapter: A Jewish Aid Worker’s Memoir of Sorrow. In 1918 to 1920, the Russian Civil War unleashed a massive wave of violence against Jewish communities by both the White and Red armies. The book’s author, Eli Gumener, worked as a representative and investigator in those years for the Committee to Aid Jewish Pogrom Victims (EKOPO) and the Russian Red Cross in the Podalia region in Ukraine.[16]

A Pedagogy: Reading as a Social Technology

What occurred on January 26 was different from your and our usual ‘shmooze.’ A shmues (Yid., conversation) is characteristically an informal and open-ended meander around a topic among equals. It’s a form of socializing that is different from an interview, a lecture, a Q&A session, or any number of ways that people can spend an hour relating to one another.

A shmues cannot take place without mutual consent. It is a social technology that embodies the essence of freedom and community, all wrapped up in a speech act.[17]

Our experimental task was to use the Yiddish writer Rokhl Auerbach’s document, Warsaw Testament, as resource to think about our feelings and impulses toward action in the early days of an authoritarian attack on liberal democracy. The task provided some discipline to anchor and relieve the discussion. It kept a timely but threatening topic from spinning off into the fear-o-sphere.

Thoughtful use of language as a tool of social organization can do this for us. Writing, reading, and discussing texts is one of humankind’s most powerful social technologies. The January 26 conversation, this article, and its pedagogy should be seen as creative deployments of basically zero-cost, non-mechanical, social technologies. With technologies like these, talk really is cheap!

Shmues, undertaken collectively with agreement to the rules of engagement, is a way to counter the narrative coming from Washington, DC, that trades in crude dualisms, bluster, lies and domination. But not everyone felt safe. We were uncertain and afraid. I was asked twice by the same person, “You’re not going to circulate the transcript, right?”

Is it possible that shmues is, itself, a form of counternarrative?

What We Know Now and What We Can’t Know Yet

In 1973, Rokhl Auerbach wrote that a writer sometimes doesn’t grasp the deeper meaning of what they want to say. For many years, she regarded her writings “about the murdered writers and artists as a memorial and requiem.” Editing what she had written twenty years earlier, her viewpoint changed: “Only as I rethought and reshaped my account did I realize that memorialization was neither my sole purpose nor the only theme of my work (p. xliv).”

These writers, artists, and public figures were starving; they were barely surviving. But what became increasingly apparent to me as I looked back was the burning dedication with which they threw themselves into their creative work and cultural activity.

Let us hope that armed resistance is not in our future. That the rise of authoritarianism in America will turn out to be a bad dream that we can awaken from intact. That our democratic institutions will be an unshakeable bulwark.[18]

Auerbach wrote:

Now I realize that armed resistance and cultural activism were not distinct from one another but two sides of the same coin: an affirmation of life in the face of death and a part of our struggle for human dignity, beauty, strength, and spirit. . . . Our colleagues, the Jewish writers and artists neither abandoned this struggle nor did they suffer defeat. They wrote, they sang, they hoped, and they believed. They have not left us. They are still here: in their legacy, in how we remember them. . .

It is not a moment too soon to read Rokhl Auerbach’s Warsaw Testament and to make good use of her legacy.

- Gelya Frank is an anthropologist, Yiddish student, blogger, and fiction writer. She is Professor Emerita, Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy and Department of Anthropology at the University of Southern California. Her email is gfrank@usc.edu. ↑

- http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100502693 ↑

- Editors, do you want references to news sources for ‘shock and awe” and “dictator on day 1” ↑

- Auerbach, Rokhl, Warsaw Testament (Samuel Kassow, trans.), Amherst, MA: White Goat Press, 2024. ↑

- Chava Rosenfarb, The Tree of Life: A Trilogy of Life in the Lodz Ghetto, trans. Goldie Morgentaler, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004, 2005, 2006. ↑

- Friedman-Cohen, Carrie. “Rokhl Auerbakh.” Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. 27 February 2009. Jewish Women’s Archive. (Viewed on February 6, 2025) <https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/auerbakh-rokhl>. Auerbach’s birthday is contested. Friedman-Cohen gives it as 1903. ↑

- See description in Anastasyia Lyubas, Blooming Spaces: The Collected Poetry, Prose, Critical Writing, and Letters of Debora Vogel, Academic Studies Press, 2020) of Auerbach and Vogel’s friendship and contributions to a modernist Yiddish cultural movement after World War I in Lemberg/Lvov/Lviv. ↑

- https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/ringelblum/index.asp?gad_source=1&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIvIG40dqqiwMVyS2tBh0N1hEbEAAYASAAEgKRD_D_BwE ↑

- Samuel D. Kassow, Who Will Write Our History? Rediscovering a Hidden Archive from the Warsaw Ghetto, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007. ↑

- The Oneg Shabbat Archive, Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-oneg-shabbat-archive#:~:text=The%20Oneg%20Shabbat%20archive%20collected,which%20more%20or%20less%20survived. Viewed February 8, 2025. ↑

- Film critic Roger Ebert writes” “One of them [members of the Oyneg Shabes] was Rachela Auerbach, a veteran journalist and critic who wrote extensively on the position of women in society and the double exclusion she experienced as a result of her gender and ethnicity. She’s an enormously fascinating figure worthy of her own film. . . .” Ebert adds, however, that Grossman pays too much attention to Auerbach to the detriment of the film and that the film’s brief reenactments of Auerbach’s relationship with Ringleblum are “two-dimensional.” https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/who-will-write-our-history-2019, Viewed February 6, 2025. Ebert’s take speaks to a larger “woman question” concerning how Auerbach’s life and work as a middle-aged and then older woman professional has been perceived and portrayed. In Warsaw Testament, Kassow writes: “By all accounts Auerbach was not a happy person, nor what she easy to get along with.” He cites to a single page in Efrat Gal-Ed, Niemandsprache: Itzik Manger—ein europäischer dichter, Berlin: Jüdisher Verlag im Suhrkamp Verlag, 2016, p. 310. In turn, Rokhl Kafrissen points out in Tablet magazine that the renowned Yiddish poet Itzik Manger, Rokhl Auerbach’s partner in a ménage, was hardly a good character witness: “Making matters worse, Oyerbakh’s ‘great romance’ was with the poet Itzik Manger. Indeed, for many years, if she was recalled at all, it was often in this capacity. She herself wondered if her career had been damaged by the popular perception of her as, in the derogatory Yiddish slang, a literarishe baylage (literary supplement), i.e., a groupie. But Oyerbakh’s relationship with the erratic Manger was much more than a fling between a famous poet and an admirer. Oyerbakh and Manger were intellectual equals and Oyerbakh put a great deal of her own energy into Manger’s work, helping him with his manuscripts and business dealings. In return, Manger, a violent alcoholic, beat and slandered her.” Rokhl Kafrissen, Buried Treasure: Rokhl Oyerbakh belatedly gains recognition for uncovering the truth about life in the Warsaw Ghetto, Tablet, November 19, 2019. https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/community/articles/buried-treasure. Viewed February 6, 2025. ↑

- The Yiddish Shmoozers (In Translation) www.yidlit.com was started by the myself and the activist Reform rabbi Haim Dov Beliak in 2018, to provide “an English-language, online conversational space to explore Yiddish literature and the arts in historical contexts and as a resource for the times we live in” (www.yidlit.com). The group is a non-profit project of the organization Friends of Jewish Renewal in Poland (FJRP) https://www.jewishrenewalinpoland.com/ of which Rabbi Beliak is founding director. An interview with Dr. Samuel Kassow will take place on April 27, 2025, in FJRP’s Freighted Legacies series. The Yiddish Shmoozers is open without charge to new members and respectful participation by the public. It aspires to promote “a non-discriminatory, multiracial/mixed race, intergenerational, gender-inclusive, politically tolerant, respectful and caring discourse.” ↑

- After the January 26 conversation I decided to submit a pitch for this article to the editors of In Geveb. I contacted each participant individually to discuss any possible ethical and political concerns related to publication and to listen for any further comments or reflections. Selections from the Zoom transcript were edited and grouped thematically for relevance, clarity, and conciseness. Participants were asked to review the article before submission for its faithfulness to their quoted speech and to its description of the session overall. No actual speakers’ names appear. ↑

- Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2017. ↑

- David E. Fishman, The Book Smugglers: Partisans, Poets, and the Race to Save Jewish Treasures from the Nazis. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2017. ↑

- Eli Gumener, A Ukrainian Chapter: A Jewish Aid Worker’s Memoir of Sorrow (Podolia, 1918-20). Trans. Michael Eli Nutkiewicz, Bloomington: Slavica Publishers, 2022. ↑

- The idea of a speech act refers to the pragmatic meaning or function of an utterance, apart from its literal content. Articulated by philosophers J. L. Austin (“How to Do Things With Words”) and later, John Searle, highlights the ability of language to do other things besides description. ↑

- Gina, an anthropologist and market researcher, provided a lengthy reflection and hopeful note after reading this article in draft. “As a Latin Americanist, I was struck by the black-and-white contrast, that either we have fascism or we have a democracy. The historical and political history differences between North America (especially Canada but also the U.S ) and the southern, mostly Spanish-speaking countries below the Rio Grande, have left us unprepared to deal with oligarchs, dictators, military regimes, absurd and mostly illegal policies and imposed actions, and the back-and-forth swings of power and politics. However, from that history, I take away the probability of change and recovery. Of multiple and evolving shades of gray. In country after country, the return to democratic forms was achieved by collective consciousness and action alongside the inexorable economic disasters that come with ideological policies and personal will. When crisis and chaos yield to change, it may be more painful than we would like and the damage done may never be fully repaired nor forgotten. Memory will not allow that. But even the most entrenched forms will eventually yield to change. Autocrats and power-seekers take their cues from those who came before. But this is not Europe in the 1930s and nothing in these MAGA policies and abuses will ‘make the trains run on time.’ Governments and regimes fall of their own failures and missteps. Often where it is least expected. It is our job to keep talking truth in our small and everyday ways. In the world shared by the Shmoozers, this will include publications and discussions and connections.”↑

Friends of Jewish Renewal in Poland Present

Freighted Legacies (Dziedzictwa obarczone): The Culture and History of Jewish Interactions in Poland

"[w]e learn history not in order to know how to behave or how to succeed, but to know who we are" (Leszek Kolakowski)

Freighted Legacies Webinar

Dr. Samuel Kassow’s Translation and Framing of Rokhl Auerbach’s Warsaw Testament

April 27, 2025 / 10AM Los Angeles / 12N Chicago / 1PM New York / 6PM London / 7PM Warsaw / 8PM Jerusalem

*CLICK HERE* TO REGISTER FOR THIS WEBINAR

FIND OUR WEBINARS ON OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL.

It’s no cost to you to help us monetize our YouTube channel.

Please click the “subscribe” button (we need a minimum of 1,000 subscribers).